|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Read Bjork's2001 interview with Juergen Teller from the index archives. |

|

|

Kathleen Hanna discusses writing and making music in this interview from 2000 with Laurie Weeks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Isabella Rossellini spoke with Peter Halley in this 1999 interview. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alexander McQueen's 2003 interview with Bjork. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

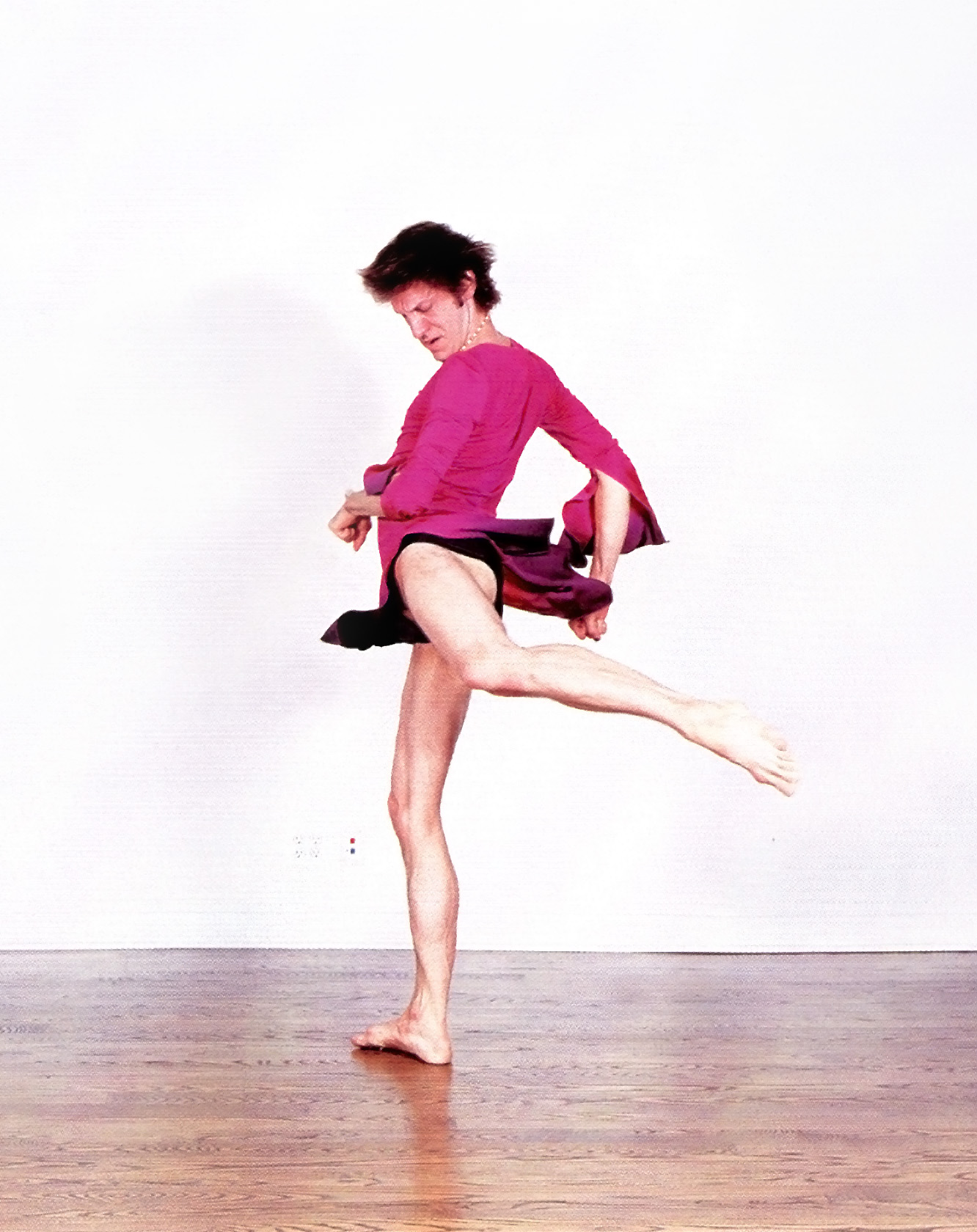

| Stanley Love, 2000

WITH BOB NICKAS AND LESLIE SINGER

PHOTOGRAPHED BY MARK BORTHWICK |

Dancers appear in index about as regularly as alien abductees, but when we saw Stanley Love, there was no turning back. Watching Stanley is practically an out of body experience: your eyes remain fixed on him from head to toe — which isn’t as easy as it sounds. At a recent performance, he took the stage with a running start and cartwheeled all the way across. The crowd broke out in whoops, hollers, laughter, and applause, and in the sheer audacity of his gesture notice was served: we’re here to enjoy ourselves, and anything can happen because everything is allowed.

Stanley’s company looks like real people really dancing. He refers to his dancers as his “material,” and through them he lets you see that dance is something we make for ourselves and share with each other. And while Stanley’s choreography feels almost purely vernacular, its roots are firmly set in the history of modern dance — talking to Stanley, you’re as likely to encounter Martha Graham as Bob Fosse.

One of Stanley’s great talents is his ability to take a song or a piece of music and bring it to life with bodies moving in space. He does it with everything from Mozart’s “Requiem” to “Rock Skate Roll Bounce” by Vaughn Mason & Crew. Stanley’s latest show-stopper is a Supremes’ medley that includes “Nothing But Heartaches,” “I Hear a Symphony,” and — how could he resist — “Stop! In the Name of Love.”

BOB: I only have one question. Tell us how you got started, make it a really long, interesting story, and tell lots of funny anecdotes along the way.

STANLEY: What’s the question? [laughter]

LESLIE: Tell us how you started out.

STANLEY: I probably started dancing socially to disco, with my mother. I used to dance with her while she was getting ready to go out.

BOB: When was this?

STANLEY: ’78, ’79 ... in Iowa.

LESLIE: And how old were you?

STANLEY: I was around nine. My mom was just getting divorced from my stepfather, so she was going out all the time. It was very disco queen, with the kids, getting ready, the single mother going out.

LESLIE: As a kid, did you do any other dancing besides with your mom?

STANLEY: In my early teens I was break dancing. And there was kind of a white grunge thing — not like Nirvana, but a pre-Nirvana thing happening in the Midwest.

BOB: What’s “white grunge?” Was there another kind that I missed?

STANLEY: There could be black grunge. But in my high school, the black kids weren’t usually grunge. They were more Janet Jackson — which was a whole other social dance scene in the ’80s, dances like the wop and the snake. I drew upon those even before I started training.

LESLIE: Which was when?

STANLEY: I didn’t start until I was seventeen. Then I came to New York a year later to go to Juilliard, in 1988. It was like boot camp. We had classes all day long for four years, all different dance styles. That’s where I got most of my technical technical training. But it was always about music for me.

BOB: A lot of what you dance to now was probably what you were listening to back then.

But you also dance to classical music ...

STANLEY: Well, for me it’s all classics. I’m rediscovering a lot of music now, too. Like a lot of the Supremes stuff.

LESLIE: How do your ideas evolve from the music?

STANLEY:Either rhythmically or emotionally, or both ... in different degrees. If it’s kind of clubby stuff, it’s about the rhythm, which would relate to the structure of movement. If it’s emotional, then it’s more about content.

LESLIE: So would a more narrative song inspire you to put a story to it? Because there’s also an element of acting that goes on in your work.

STANLEY: There’s some acting. This season I’ve been trying to be really literal with the arm gestures in relation to the words — it’s almost like drag queen dancing — especially because of the Supremes’ lyrics.

BOB: I look at some of the acting in your work as “bad acting.” To me, it comes from silent movies, where the actor’s gestures and facial expressions are intentionally exaggerated. But it also comes from disco, where the emotions are amplified, and everyone’s a drama queen.

STANLEY: Well, in silent films, all they had was being physical. I think a lot of the people who dance for me make that choice to be more physical. So it is over-theatrical in certain sections. I encourage them to be physical even though it can be interpreted as bad acting. For some of them, it’s real. And others enjoy the melodramatic. Some of them are more actors who dance, and some are more dancers who act. I let them be their own flower.

BOB: So they can amplify things without your saying, “Here’s exactly what I want.”

STANLEY: You’ve had an idea, and then everyone has their own way of doing it. And when you go back again to rework it — I guess that’s when I feel more like a director than a choreographer — you make a choice: “Where am I going to snip?” Like bonsai. That’s where you unify things. But you can’t touch everything. So you have to decide what you’re going to let be more wild — like part of your garden — and what’s going to be the more structured part of your garden. I let the wild parts stay. That’s also why I try to have my dancers move differently.

BOB: Their movements aren’t all perfectly in sync with each other — which really makes it feel like people dancing.>

LESLIE: Now, you started your company right after graduation?

STANLEY: Yeah. In the beginning, it was just all my friends from school, and the first thing I did was a piece with seventeen people. So I started on a large scale, mostly with Juilliard people.

LESLIE: We heard that you did an amazing job trying out for Elizabeth Streb, and about how much she loved it.

STANLEY: I spent the entire first day slamming up against a ten-foot tall plexiglass wall. I came back the second day with these huge blisters, and they broke. I couldn’t move my hands. I couldn’t even change my clothes.

LESLIE: Well, Streb says that she does things that people could get killed doing.

STANLEY: I think it’s about impact. Some of these things look like they’re impossible to do, but it’s very high-level, fast space awareness. And they have ways to fall. They have techniques.

BOB: So you endured two days of all this extreme stuff?.

STANLEY: And they asked me to stay — I just didn’t go back.

BOB: Why not?

STANLEY: Because I didn’t want to deal with broken up hands. At the audition, they said, “We don’t wait for the violins to come in here” — meaning they don’t have music. But I would rather wait for the violins to come in. [everybody laughs] And I already had my own dance company.

LESLIE: But Streb’s amazing. She’s pretty out there wild.

STANLEY: She’s opened up so many ways of looking at what the body can do with space — just space and the body. I was only there two days and it’s still in my body. That’s another reason I don’t dance for other people. No matter what you do, their movements are in your body because of muscle memory. I’ve worked hard to try to even get rid of a lot of my Juilliard stuff.

BOB: It was great to be at the rehearsal the other day. When the dancers went through a piece on their own, and you knew something was missing, you’d come out and show it to them. It was like somebody just pulled out the blueprint for the house; the movements became crystal clear.

STANLEY: I can’t always do the steps myself. There are some I guess I just don’t learn. Or it would take a lot for me to learn. Lauri is my dance captain and she remembers all the steps. She knows almost everybody’s steps from the last eight years.

LESLIE: As dance captains do. Now, you mentioned trying to forget what you learned at Juilliard. Was that another impulse for working with non-dancers? People who weren’t so ingrained with some dance memory?

STANLEY: No. The non-dancers were all personal friends who wanted to be part of it.

BOB: But did you say “yes” to everybody?

STANLEY: I would, and there have been times when I had thirty people in a piece, but not everybody works out. And that just takes so much energy that my energy gets spread thin. I’ve decided to condense for right now.

LESLIE: And work with a core, trained group.

STANLEY: Yeah.

BOB: What happens when the company dancers literally bump up against the people who work a little more loosely?

STANLEY: That was a problem. Although the dancers are usually nice about it because they’re mostly friends — “Oh, that’s Edie’s boyfriend.” And I try to make those group dances about universality. So the movements are simpler. One was done to the end of a Chaka Khan song, and they just moved their butts in a circle, a whole group of people doing that.

BOB: Who can’t do that?

STANLEY: It was minimalistic ... just a nice beat and rhythm, and everyone could dance to it.

LESLIE: Have certain choreographers been an influence?

STANLEY: Well, in my piece which uses “The Rose,” by Bette Midler, I purposely referred to ’30s or ’40s modern style, like Martha Graham or Doris Humphrey — with really weighted, overdone gestures ...

LESLIE: So your work is coming out of people like Doris Humphrey and Martha Graham.

STANLEY: Well, José Limon wrote a piece for Doris Humphrey called “Choreographic Offering.” “The Rose” was my choreographic offering to my dancers.

BOB: But what’s the link to that Bette Midler song? In the movie, The Rose, her character is based on Janis Joplin.

STANLEY: On the same program, we also do Judy Garland, with “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” and Nirvana, with the opening of “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” But “The Rose” started it off. It’s about the artist as martyr probably.

BOB: Those are all tragic figures — Janis Joplin, Judy Garland, Kurt Cobain ...

STANLEY: I’ve always used Judy for that, and I use Kurt against Judy because they’re both suicides. “The Rose” is about the most extreme artists; they do their art until the end and then kill themselves. And then we do “Requiem” at the very end, which is Mozart’s “Requiem.”

LESLIE: That’s beautiful. And one of the great things about your work is the repetition. Sometimes you repeat a piece three or four times.

BOB: When a piece goes by quickly, with a lot of dancers to follow, it’s great to get an instant replay — though you sometimes make it slightly different.

STANLEY: There are a lot of reasons for doing that. Just so people get to watch it again. And I’m going to see what that brings on. It might be too much but I’m still going to try it.

BOB: It seems like a cliché to say that when you watch dance you literally “see the song.” But it really struck me at the rehearsal — I think during the Supremes’ “Stop in the Name of Love” — that the dance was almost like signing, you use hand gestures to speak. I could completely follow the lyric and the emotions through the gestures of the dancers.

STANLEY: Definitely. A lot of this — especially with the Supremes stuff, is almost like dance lip-synching. I’ve always had a tendency to be overly literal, especially with pop music, because it’s so obvious anyway. I think the Supremes might be the height of my ...

BOB: Literalness?

STANLEY: Yeah — with gestures and words. I do that with the Supremes because it’s older music. Everyone has heard these songs, so at the start of the evening it helps set up the aesthetic ...

LESLIE: Or at least clues you in on what to look for.

STANLEY: Yeah. Because there are a lot of cuts in the narrative that don’t make any sense. We just keep moving on to a new subject, new subject, new subject.

LESLIE: Some of your references aren’t as familiar or as visible. Like the ones from movies. I know you’ve talked about Fame and A Star Is Born.

STANLEY: A Star Is Born was just one image. I use a lot of images with each move. We’ll often have ten different images for one move.

BOB: What do you mean — ten different images for one move?

STANLEY: I might say, “Can this one be half A Star Is Born and half Norma Desmond from Sunset Boulevard?”

BOB: And they know what you’re talking about?

STANLEY: Yeah. And they’re able to do that.

BOB: Wow.

STANLEY: And I might even ask for a dash of Carol Burnett. I mean, it could be anything. It’s always an engagement — or a conversation. They ask questions if they’re not clear, and we talk about it. And now, since I’m working with more evolved dancers — I guess dance dancers, I’ll call them — it’s a lot easier.

BOB: At your rehearsal we both got copies of a really great dance zine called High Ass. A dancer wrote a piece about being called in to audition for a Gap commercial, and he was thinking, “What am I doing here?”

LESLIE: I think it’s the commercial that was like a scene from West Side Story.

STANLEY: I’m not sure if that’s the one, because I went to the same audition.

BOB: You did?

STANLEY: And it was different music and a different choreographer. It made me depressed. And I was already depressed because they’d stolen from Bob Fosse’s Sweet Charity. It was a total rip-off.I mean, I don’t think anyone really invents movement. I think everything’s been done before. But just to rip off exactly, from the beginning to the end, it really kind of makes me ill. And I think they did that. Now that Fosse’s dead, I don’t want to go see any Fosse. It’s the same reason I don’t see Graham now.

BOB: Do you think the dance is alive only if the person who made it is still there?

STANLEY: There’s an element of that. But even if it’s already choreographed, it has to be directed. So who’s going to do that? There’s this whole process of how it’s handed down. Like, what is dance history? It’s mostly lost. Fosse’s work was genius. His directing was as important as his choreography, and if he’s not there, a lot of the genius is gone. It’s not just the dance steps.

LESLIE: Merce Cunningham is doing dance on the computer now, and everyone says that’s so great because it’s going to be preserved. But it’s just the steps. You’re right. Direction is such a key part of it too.

STANLEY: It’s possible to train someone and have the training last for maybe twenty or thirty years. And it’s still somewhat of a carbon copy, because only Merce would be able to say, “Okay, at this exact second, I’m going to roll these dice and mix these people up and make them a little bit nervous right here.” He’s still doing that. And once he’s gone, that’s gone. No one has his impulses but him. So that’s why I haven’t seen any of the redone Fosse. What I’ve seen is so precious to me, I don’t want to risk it being tainted.

BOB: Do you mind my asking why you went to the audition for that commercial?

STANLEY: I hadn’t been to an audition for so long that when the call came I decided I would go. Because it was Gap I thought it would just be hilarious if I actually got it.

BOB: You could call it research.

STANLEY: Commercials are good jobs. You work for two days, you make a lot of money. And you’re not doing anything. That’s like the best job in the world, as far as time and money. I went because they called, but I don’t go looking for them.

BOB: And if you got the job, people in the dance community would say, “I was watching TV and there was Stanley, whizzing by in a Gap commercial.”

STANLEY: A lot of dancers have done pornography work, so I think compared to that, it really wouldn’t matter. [laughs]

BOB: But that brings up something else from High Ass. One of the dancers talked very candidly about being a sex worker, and being able to subsidize his dance career. Because obviously, dancers just don’t make any money.

STANLEY: I know who this person is, and so do other dancers. We’re all fascinated by it and ask him lots of questions about it.

LESLIE: I’ve known dancers who’ve stripped ...

STANLEY: Stripping is very different than sex work. And they’re both rough in their own ways. Each of them has a different energy involved. The guy we’re talking about turns tricks – and he sets it all up on his computer. I knew him before and after, and he has an independence he didn’t have before. He’s very happy doing this, whereas most dancers I know are kind of sad and angry.

BOB: I don’t know how you do it, Stanley. You have to assemble this group of people, find a space to rehearse, and hold it all together.

STANLEY: It’s a garden that I got a long time ago, and I’ve just kept watering it. Do you know what I mean? I’ve been doing it since school, and I think if I would have stopped and then restarted later on, it would have been very different. I think somehow there was some momentum ...

BOB: Until now, the shows I’ve seen were in galleries and they were free. But free doesn’t pay the bills. So what are you doing for this new series of concerts?

STANLEY: This time we’re charging at the door, which we haven’t done for a year.

BOB: If you weren’t going to, I’d take the money from the people myself and give it to you.

STANLEY: I do feel differently about what I’m doing when I charge. If I don’t, there’s definitely a freedom ... I don’t feel that I owe the audience anything. [laughs]

BOB: In the piece, “Let’s Be Friends,” the dancers seem to meet and become attracted to each other. It really makes me think about how, for you, dance is something that people make with and for each other.

STANLEY: Dancers are definitely social. The first half hour of my rehearsals is always just people sitting around and talking. It’s supposed to be warm up time ...

LESLIE: Well, that’s how they warm up.

STANLEY: Yeah, it is. If they’re going to move together, it’s important that they know each other. I can’t do anything with an unhappy dancer. I guess I could, but I’d rather not. I think that the medium is people above all else — and a boom box in a space.

BOB: To me, it looks like real dancing. Which says something about your work being vernacular. I don’t mean to offend anyone, because I find all your dancers interesting to watch. But you’re definitely not showing us a line of perfect, identical bodies.

LESLIE: Pina Bausch, as an example — all her dancers have the same body type, the same long arms. Your dancers are more like pieces in a puzzle than carbon copies, one after another. There’s more individuality and more texture.

STANLEY: We are a Manhattan-based company. [laughs] But for other choreographers it’s their look, and it adds something if everyone looks the same. There’s a power to that too. As far as people coming in all shapes and sizes, I like having people who are more human.

BOB: I think your use of disco also affirms a general sense of liberation. Like when you do that great Chaka Khan song, “I’m Every Woman.”

STANLEY: For me all music is liberating. When I’m dancing it’s liberating, whether the music is happy or sad. Everything I do is about the performance. So when you’re in it, it’s the most freeing place.

BOB: With disco there’s also an element of escapism ...

STANLEY: To go outside every day and experience great joy in moving for an hour is wonderful. And I don’t see it as throwing my life away — like frolicking. I mean, if it is frolicking, it’s fine. But sometimes it’s frolicking and sometimes it’s sorrow.

BOB: You talked about repetition. But you also dance to snippets — short bursts of music, like thirty seconds.

STANLEY: Well, a lot of them are just beginnings of songs. It’s like a sample sale. We’ll make a phrase, and work on it, and once it looks okay, I won’t go on. And that’s as long as that phrase is going to be.

LESLIE: You’ll end up with a number of them?

STANLEY: Yeah. And we’ll do those phrases every rehearsal. So then each one gets just a little bit longer. And some come out real easy and some ... don’t. [laughs] I never have enough time to finish all the songs all the way through. We’d need to be a full-time dance company, paid. Then I could do an evening of whole songs.

BOB: Are there any dancers right now who inspire you?

STANLEY: Oh, I don’t know. I guess I’m not inspired by dance so much. I’m more inspired by dance floors.

LESLIE: Do you ever go out dancing in clubs?

STANLEY: Well, I haven’t so much for a while because they’ve kind of died. Maybe I’ve gotten older, but it seems like there are fewer clubs and it’s more difficult to have a good time. And the music has changed. It’s more computerized now. I like human beings playing instruments. So I don’t go out as much. It’s coming more and more from memory. And the more time I spend with my dancers, the less time I want to go out dancing at night. Also, in a lot of bars now, it’s illegal to dance.

BOB: They need a cabaret license.

STANLEY: Which is really expensive now. It’s like you have to pay the government to have dancing be legal. I just don’t get it.

BOB: I was dancing with friends in a bar and we were told to stop.

LESLIE: It’s happened to all of us.

STANLEY: It’s so disturbing to me. This thing that’s like my religion, that I devote my life to, can be illegal. I feel like I could be arrested, especially when they have signs as big as a window — “No dancing.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

©

index magazine

Stanley Love by Mark Borthwick |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2008 index Magazine and index Worldwide. All rights reserved.

Site Design: Teddy Blanks. All photos by index photographers: Leeta Harding,

Richard Kern, David Ortega, Ryan McGinley, Terry Richardson, and Juergen Teller |

| |