|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Read Bjork's2001 interview with Juergen Teller from the index archives. |

|

|

Kathleen Hanna discusses writing and making music in this interview from 2000 with Laurie Weeks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Isabella Rossellini spoke with Peter Halley in this 1999 interview. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alexander McQueen's 2003 interview with Bjork. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

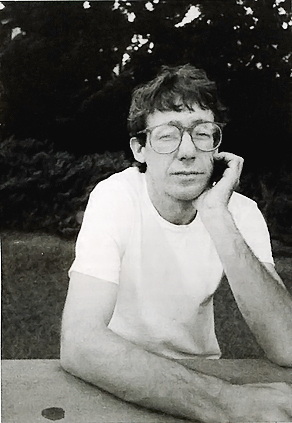

Charles Ray, 1998

WITH DENNIS COOPER

PHOTOGRAPHED BY JOEL WESTENDORF |

At 44, Charles Ray is without a doubt one of the most influential contemporary artists. His trippy, sublime work has been more often reproduced and discussed than experienced, but a mid-career traveling retrospective, scheduled to open at the Whitney Museum in June, will unite his small and meticulous output for the first time. When I grabbed Ray for a conversation, it was three weeks before his latest piece, Unpainted Sculpture, was scheduled to open at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, and he had been putting in daily eighteen hour work days for months. We sat down for a coffee at a diner near his studio in El Segundo, a small beach front community just south of Los Angeles.

DENNIS: So how tired are you?

CHARLES: I'm pretty tired.

DENNIS: Can you remember how you got the idea for Unpainted Sculpture?

CHARLES: Well, I was working on the Fashions film. I hadn't actually made anything in a long time, and there was a catalog that got sent to me from a show. One of my big mannequins was on the cover. I saw her hand out of the corner of my eye, and I remembered working on that hand, and its spatiality. It made me yearn to work on something with form again. Then later that week, I was out to dinner with the young artist Tim Rogeberg, who was my student at the time, and some other people, and Tim's car was smashed up. He was debating whether to take it to the body shop, and I said, "Why don't you just take a fiberglass mold of the wrecked fender and put it back on?" It was sort of a joke, but Chris Finley was with us, and he said, "That would be a good piece for you to do, Charley," and it just stuck with me. So that was the entrance.

DENNIS: But at some point it became about death too.

CHARLES: No, never per se about death. I spent a couple of months looking for a wrecked car that was really sculptural. I went to all these insurance yards, and I was looking at ones in which fatalities had occurred. I don't believe in ghosts, but I wondered that if there were ghosts, would the ghost inhabit the actual physical molecules of the structure, or would it be more interested in inhabiting the topology or the geometry of the structure? You know, if you were to duplicate the geometry, would the ghost follow?

DENNIS: Do you think it has in some way?

CHARLES: When I first got the car to my house, it was all bloody, and it had much more of her presence then, I think. What's more interesting to me than thinking about ghosts is thinking that that car had a whole life. When we took it apart, we saw evidence that it had been in a serious accident before the fatal one. I figure it's starting its life over again as an art object. I think about its life - from the factory in Detroit, through the wrecks, then ending up in my hands, and now it's ended up in another weird assembly line in my studio, and it's going back out again. It has a funny trail of identity.

DENNIS: Did it give you pause when Princess Di died in a car wreck?

CHARLES: No, no. It more gave me pause when I heard they were making a movie of Crash. Ballard was a big influence on me, but not in terms of this project. More in terms of the figurative work, the relationship between sex and technology. My fear was that the piece would be seen as like an advertisement for the movie, but I got over that, and now I'm interested in the topicality of the car wreck as a counterpoint to the abstraction. The piece has wound up being really abstract. It's moved away from the specific.

DENNIS: Do you find that, knowing about the possible misassociation with Crash, you've consciously covered your bases, either in the conceptualizing or in the physical construction of the piece?

CHARLES: The only thing that covers the bases really is the title, Unpainted Sculpture.

DENNIS: What about the decision to make it gray? Originally you were going to replicate the look of the original car, paint and all.

CHARLES: The decision to make it gray was a long time coming, through a reckoning with the form. I started to think of it as like the fade-ins and outs in movies, because a lot of it is sort of blank, like a pause. Part of that decision was due to financial limitations, but it's a better piece for the decision. I think the piece has my very best and my very worst in it. It has a bit of my showoffiness, and my sensationalism and grandstanding. Like everyone told me, "It's impossible. You can't take a mold of a wrecked car like this." And I said, "You can. You have to think of it as a thousand small sculptures." That's what we did, made a mold of every piece and assembled it back together. So it has my worst, like I said - my showoffiness - but it also has my best, I think, in its uncanniness. I hope it draws people in.

DENNIS: There was a period of years in the early '90s when you hardly did any work, after Family Romance and before the sculpture of yourself in the bottle. What happened?

CHARLES: I quit smoking, and I couldn't concentrate. And I had a survey show in Europe that took a lot of my time. And I was finished with the figurative work, and I just needed to rethink. I needed to hit a brick wall and start over. It was a struggle, a fallow period. I was trying to find an entrance back in somehow.

DENNIS: Were you depressed?

CHARLES: No, it was boring. I was frustrated with the art world, frustrated with people wanting things.

DENNIS: You stopped being associated with galleries around then.

CHARLES: I still work with galleries, but I stopped having a primary gallery right before the lull. I just needed to be independent. That's all there was to that decision. Really, I'm sorry, no big mystery there.

DENNIS: I get the feeling that music helped you regain your footing. Because you didn't listen to music at all for most of your life, right? I remember you saying you didn't understand music. I'd play you CDs and you'd just look perplexed. But then you suddenly started buying CDs and playing them while you worked, and you'd ask me to give you tapes of different bands I was listening to.

CHARLES: Yeah, that made a difference, but I'm sort of over music now. I was really into music for a year, but I haven't really listened to much for seven months now. I only listen to what the people helping me with the car play. Like my friend Peöa and his son listen to Mexican music, and some of the younger people listen to Built to Spill and that sort of stuff.

DENNIS: Why did music fascinate you for that year?

CHARLES: Well, you and my other friends all listened to it, and I thought I'd try it too. I remember you showed me some ABBA videos and that sort of started it, thinking about the form and space in the videos. But I got interested in the idea of singer-songwriters mostly, people making up lyrics.

DENNIS: How did it feed your work?

CHARLES: I was interested spatially, like what was the space of music? What kind of physical and mind space did music occupy? I was sewing clothes a lot during that period for the Fashions film and another film I'm still working on, and the intangible space of music seemed to relate to the intangible space inside a 16 mm film, which seemed intangible to me. I thought that there was a physical space to music, and I was trying to find it. I was and still am very naive about music, so I picked up on music where I'd left off years before - things like Dylan, songs with words. The Beach Boys, Van Dyke Parks.

DENNIS: So did you find the space?

CHARLES: Yeah, but it's intangible, like I said. I'm really interested in physics, and it was similar to that. I can't really find anything in particle physics that is similar to my work. A particle physicist isn't going to find anything in my work that he can take back and use to tear apart the atom. Nor am I going to find anything in tearing apart the atom that I can use. It's just inspiration. In and around physics and music is something very meditative for me.

DENNIS: But why singer-songwriters? Why couldn't we get you interested in, say, Orbital or the Future Sound of London in the same way? I mean, you talk about spatiality - techno is all about issues of organizing space.

CHARLES: I don't know. The singer-songwriters always seem to have more urgency, singing about their lost girl or suicide, you know? The emotional space there, I like that, and I find something similar in physics. But, you know, I have to say that I was listening to "In A Gadda Da Vida" on the radio the other day, and I was thinking how beautiful it was that "In A Gadda Da Vida" was once somebody's work. That was once the space of somebody's work. I like thinking about oldies that way, because the old farty stuff has a time dimension in them that new music doesn't have.

DENNIS: If you ever get a MacArthur Genius Grant, what will you do with the money, do you think?

CHARLES: How much are they?

DENNIS: Well, Vija Celmins got something like $280,000.

CHARLES: You can do whatever you want with it?

DENNIS: Yeah. Jennifer said you'd probably buy a boat.

CHARLES: I might, but you can't really buy a great boat anymore for that kind of money. They cost like, half a million. You could buy a second-hand boat, I guess.

DENNIS: What do you think your intense love of boats and sailing is about?

CHARLES: It's just bitchin. Sailing is like drugs in a way. You can be very far out to sea, and you can't just say, "I'll go in now," when bad weather comes. It's like a bad acid trip. You can't say, "I didn't take the acid," and get over it, because you did take the acid. You are out there. I like that. And it's like an art. It has a properness to it. It's you and the sea, the sea and the boat. There's a harmony when everything's going right. Everything's being rewritten all the time. You're always challenging yourself physically and mentally. It's beautiful. It's like instant wilderness.

DENNIS: Who are some contemporary artists you've been thinking about lately, if any? I mean in an appreciative way.

CHARLES: I really liked the Gober show at MoCA a lot. I really respect how his work is developing. I like Jeff Koons. I think Koons's work is really sculptural, and a thousand years from now when the cultural patina wears off, there'll still be something really beautiful there that has to do with form. Take those big flower arrangements he made. They're like great Constructivist sculptures. Your mind just goes in and out between the flowers. It's very powerful.

DENNIS: Do you have a favorite piece of your own work?

CHARLES: Not per se. It shifts. It's more that if my older pieces don't work in an interesting way, their problems interest me and seem meaningful. It's a good problem that opens the door for me to go somewhere else and resolve the problem in a way. Like Family Romance resolved the orgy piece Oh Charley Charley Charley ... for me, and the boy resolved the big lady.

DENNIS: Where does the Fashions film fall in all this?

CHARLES: Well, it resolved the self-portrait in a bottle piece. My real interest there had been trying to make an abstract sculpture in a bottle, but I never could, because I kept bumping up against genres all the time. I kept thinking it didn't look as good as a boat in a bottle, or it would just look like a weird boat. So I ended up doing a self-portrait, the figure of me, which for me was about the space inside the bottle. So that led to thinking about putting Frances Stark, who appears in Fashions, inside the space of a 16 mm film, which is kind of an abandoned medium too. People don't build boats inside bottles anymore, and they don't really make 16 mm films either.

DENNIS: So it wasn't about fashion itself? It wasn't related to the edition you did for Parkett where you made snapshots of supermodel Tatiana?

CHARLES: No, you always need a reason to work, and Frances was working for me that summer. She's a girl. We had this idea of building clothes on her. That was pretty much it.

DENNIS: Have you followed Tatiana's post-modeling career in TV commercials?

CHARLES: No. I haven't watched TV in like, eight years, except at your house, and then I always fall asleep.

DENNIS: Almost immediately. You fall asleep in movie theaters too, and yet you go see movies all the time.

CHARLES: I like films a lot, just the scale and the space and the cultural aspect of seeing films. It seems like the last civic thing we do.

DENNIS: You're on sabbatical from UCLA this year, but teaching there has seemed to be really invigorating both to you and to your students, who are really bursting into the art world of late.

CHARLES: I don't know about them being invigorated, but yeah, it's been great for me, especially in the past two years or so. The school is full of energy, and I've gotten older to the point where I'm starting to see things that aren't clearly second or third generation off my generation's work. I'm just beginning to see things that I'm really unfamiliar with, that aren't post-conceptual or post-minimal anymore, and that's exciting. I really feel like the students are teaching me.

DENNIS: Teaching you what?

CHARLES: I don't know. You can't really pinpoint stuff like that. For one thing, they work really hard, and, speaking of which, I've got to get back to the car and the crew.

DENNIS: Okay, but before you go, people who know you well know that you are absolutely fascinated by telling and hearing jokes. So tell me one.

CHARLES: Okay. Wait, how does it go? Oh yeah. A panda bear walks into a Chinese restaurant. He orders his meal, eats, and when the waiter shows up with the check, he pulls out a gun and kills him. As he's leaving the restaurant, the maitre d' runs up to him and says, "My God, what have you done?" The panda bear says, "I'm a panda bear. Look it up in the dictionary." So that night when the maitre d' gets home, he pulls out a dictionary, and looks up panda bear, and it says, "Panda Bear, marsupial, native to China, eats shoots and leaves."

|

|

|

|

|

|

©

index magazine

Charles Ray by Joel Westendorf, 1998 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2008 index Magazine and index Worldwide. All rights reserved.

Site Design: Teddy Blanks. All photos by index photographers: Leeta Harding,

Richard Kern, David Ortega, Ryan McGinley, Terry Richardson, and Juergen Teller |

| |