|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Read Bjork's2001 interview with Juergen Teller from the index archives. |

|

|

Kathleen Hanna discusses writing and making music in this interview from 2000 with Laurie Weeks. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Isabella Rossellini spoke with Peter Halley in this 1999 interview. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alexander McQueen's 2003 interview with Bjork. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

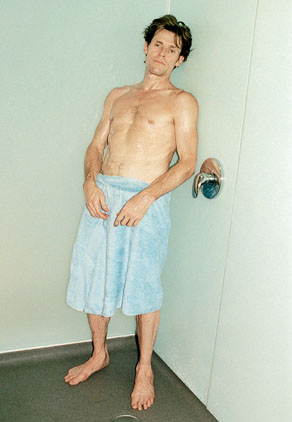

| Willem Dafoe,2003

WITH JUSTIN HAYTHE

PHOTOGRAPHED BY JUERGEN TELLER |

Willem Dafoe is weirdly sexy.

His movie roles include Jesus and the green goblin.

On stage or on screen, you can't take your eyes off him.

Next year, Dafoe will appear in the psychological drama The Clearing with Robert Redford and Helen Mirren. Here he talks to Justin Haythe, The Clearing's screenwriter, about the perils of relaxation and the best way to hunt for mushrooms.

(Haythe met Dafoe near a summer place in Maine that the actor shares with his partner, Wooster Group director Elizabeth LeCompte.)

JUSTIN: How much preparation do you do for a role?

WILLEM Most of the work happens when you're on the set. It's like going to a cocktail party — you know who's going to be there, you have certain expectations about the topics of conversation and the social dynamic. At the same time, when you arrive, you've got to be able to abandon those preconceptions and be mercurial. But sometimes the most important thing is just having a good costume. [laughs]

JUSTIN: In The Clearing you play what I hope is an unusual character — an average guy, Arnold Mack, who covets the success of another man, played by Robert Redford, and commits an extraordinarily cruel act against him. How did you approach playing Arnold?

WILLEM It was a rich fantasy to imagine myself as a regular guy with lots of thwarted ambition. And you can always draw from real life. I'm making a movie with the movie star Robert Redford — he's like the rich guy, I'm like the blue-collar guy.

JUSTIN: When your characters first meet, Arnold claims that they've met before, and after a brief pause, Redford's character, Wayne, pretends to recognize Arnold so as not to be rude. You know that in his real life Redford has had to do that a million times.

WILLEM Yes. You need moments like that to act as signposts. Your screenplay was very lean on description, but there are these tiny actions that take on huge weightƒ like when my false mustache comes off.

JUSTIN: Arnold has assembled a disguise in order to commit this crime, and then his mask begins to slip.

WILLEM That's a key event. As an actor, you can't wait to figure out how you're going to approach those moments, and how you're going to get out of them.

JUSTIN: I was on the set for most of your portion of the filming, and I worked with you on some of Arnold's dialogue. In one scene you felt uncomfortable with some of the phrasing, but then you changed your mind and delivered the lines beautifully. In the lunch scene there was another moment that you didn't like, but they didn't change the dialogue. It turned out that you were absolutely right — they ended up cutting around

it because it was a mistake.

WILLEM Sometimes you just feel like a phrase isn't part of the fabric. It's like a stain.

You want to remove the stain unless the scene is going to be about the stain. On the other hand, I think actors sometimes have too much power to take away their own obstacles. I've seen that a lot — someone doesn't feel comfortable with something, so it gets changed. But if you give up the challenges, you may be pissing away an opportunity to get something unexpected.

JUSTIN: How much do you go with your first impulse when you play a film scene?

WILLEM There are very good things about a first impulse, but sometimes it's limited. In the movies you're dealing with first experience. You play a scene for a day, never to return to it again. In theater, you return to a scene and refine it over and over. Your associations get compounded and deepened. There is no way you can get that in a movie.

JUSTIN: Outside New York you're known primarily as a film actor, but working in theater is such a large part of your life. How did you first get involved with the Wooster Group?

WILLEM I went to a Wooster Group production called Rumstick Road in 1979 — I had never seen anything like it. When I entered the tiny upstairs space at The Performing Garage I was so excited by what I saw that I wanted to be in that space, with those people, and doing those things.

JUSTIN: Can you describe the performance?

WILLEM It didn't remind me of anything — it just was. The show had the morphing fluidity of a Max Fleischer cartoon, along with the personal mysteriousness of a David Lynch film. The performers were such romantic figures to me — detached but deeply committed to what they were doing, technically in control but somehow reckless at the same time. The precise mix of all the elements somehow had an open-endedness to it. Something was being worked out in front of me. That performance was also the first time I saw Elizabeth LeCompte. I basically started hanging around the theater and insinuating myself into the fabric of the place. [laughs]

JUSTIN: Were you also thinking about doing film?

WILLEM Being an actor meant theater to me at that point. I had always liked movies,

but I didn't know anybody working in film. To do movies you had to go to Hollywood, get headshots, knock on doors, and schmooze people. I was interested in being an artist. [laughs] But that same year, someone saw me in a Wooster Group production called Point Judith and asked if I wanted to be in a movie, The Loveless. I liked the script and the people involved. At that point I had been a glorified extra in Heaven's Gate — and gotten fired.

JUSTIN: Did you have a big part in The Loveless?

WILLEM I was the central character. It was a motorcycle movie, but very self-conscious and stylized, with arch, terse dialogue bordering on parody, and a little Douglas Sirk-inspired melodrama thrown in. There was a great, repressed passion in it.

JUSTIN: How did the Wooster Group respond to your venture into film?

WILLEM Liz's genius is that she will work with whatever is there. The good news and the bad news is that she's perfectly capable of making work without me. [laughs] And when I go off to do movies, I often bring things back. On my first visit to Japan for a movie, I discovered Noh theater, which I then introduced to Liz. Of course it functions the other way, too — the experience of working on new shows impacts how I approach my movies.

JUSTIN: I had never been on a film set before the shoot of The Clearing, but from what I saw, it seemed antithetical to creating something in the moment. It felt very far away from theater.

WILLEM Theater is the one art form that incorporates what is happening now. The beauty of theater is its temporality. On a stage, you're more likely to tap into a primal present-mindedness.

JUSTIN: During the filming I was struck by the distractions between takes, whether it's people winding your watch, changing your sandwich, or doing your hair.

WILLEM I like to embrace the distractions so that they become part of my structure. I can set up the scene a little bit better if I handle my own props. Then when the camera rolls I'm totally free.

JUSTIN: It also seemed to me that you had a very disciplined way of turning off your character between takes and then turning it on again with the same level of energy.

WILLEM I feel like actors who try to stay in the mood between takes become rigid and stop listening. You've got to love the frame, and the frame is activated by the camera. Between takes, you're collecting information, you're just living. Living is good for the scene.

JUSTIN: So you're trying to stay fluid.

WILLEM Yes, but you have to be wary of the prize you get for being too emotionally fluid — take tears, for instance. An audience is used to getting involved in a story through tears. It's almost Pavlovian — if I'm crying, you start to get weepy yourself. The second I begin to go in that direction, I run away from it. I try to cultivate a suspiciousness of what I know. Hearing myself talk about this stuff I'm like, "Oh, you prick." [laughs] Sometimes you're just trying to remember your lines and unwrap the sandwich gracefully.

JUSTIN: The waiting around in trailers is a big part of life on a set. Does that affect your performance?

WILLEM I like to be on the set, in the world of the film. Practically speaking, if you're in your trailer, you don't know that the director of photography just had a fight with the director, and that's why everybody is acting so strange. You want to know that the focus-puller is fucking up, because it all factors in.

JUSTIN: My impression is that actors are somewhat isolated from the crew. No one wants to disturb an actor, and they don't want the actor to get in the way. It seems a bit lonely.

WILLEM I never think of it as lonely. I don't know how much I want to admit to liking this, but as an actor you're handled, you're touched, all the attention is directed towards you. Everything is amped up a bit. It's no accident that a lot of actors are drug addicts and

alcoholics with shitty personal lives — it's hard to go in and out of those modes. If you want to know what lonely is, go talk to those guys who are sitting around their Hollywood homes doing coke off a hard body when they're not working. [laughs]

JUSTIN: What role do your demons or fears play in your process?

WILLEM Sometimes when you allow the demons in, you find yourself. But you've got to know when to relax and when to invite that tension.

JUSTIN: I've always thought learning your craft was a way to keep the demons at bay.

WILLEM When I was younger, I thought that "craft" was a dirty word — it seemed like something people cultivated so they could perform the way a cobbler makes shoes. Now I'm starting to warm to the idea — it's nothing more than a familiarity with certain tendencies you have and how your brain works. As I get older, I'm less interested in regressive impulse and more interested in clarity and articulating my actions. "Time is running out. You've got to get it together" — said on my forty-eighth birthday.

JUSTIN: I find that building up craft is almost a form of exercise.

WILLEM Everything is practice. It's good to have a physical practice to remind you of that fact. The other day I was hunting for mushrooms. I thought there might be mushrooms around because it had rained a little bit, then it got sunny, and then it rained again. I looked around very casually. I saw a beautiful patch, and I got all excited. I found quite a few mushrooms, gathered them up in my shirt, and took them back to the kitchen. I bragged and said, "Look at all these chanterelles I found." Then, today, when I was waiting for you to arrive I thought, "I know I can find lots of them." Once I had that expectation, I couldn't find a single one. But when the expectation waned, sure enough, there they were. |

|

|

|

|

|

©

index magazine

Willem Dafoe by Juergen Teller, 2003 |

|

©

index magazine

Willem Dafoe by Juergen Teller, 2003 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Copyright © 2008 index Magazine and index Worldwide. All rights reserved.

Site Design: Teddy Blanks. All photos by index photographers: Leeta Harding,

Richard Kern, David Ortega, Ryan McGinley, Terry Richardson, and Juergen Teller |

| |